Current fiber-optic cable systems could be leveraged to create a cost-effective, real-time ocean-to-land observatory, providing the possibility to monitor everything from ships, to earthquakes, to whales. A total of over 1.2 million kilometers of fiber-optic cables run across the globe, transmitt

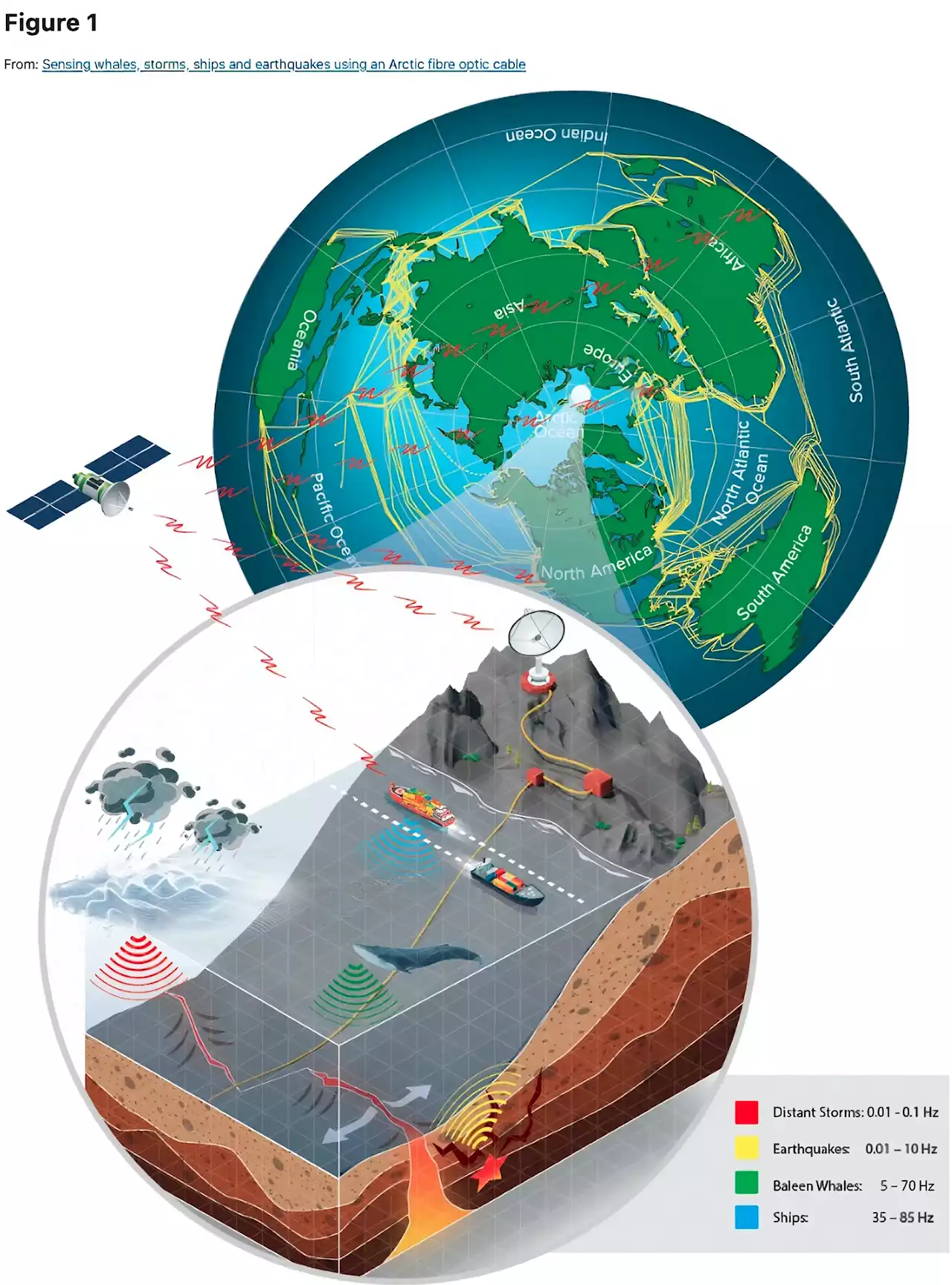

The Earth-Ocean-Atmosphere-Space observatory concept. The upper-right-hand globe shows the extensive network of existing Fibre-Optic cables . The lower-left zoomed inset illustrates the key features of the observatory and its capabilities, including the DAS detection, tracking, and identification of whales, ships, storms, and earthquakes, processed in real-time, fused with other sensing sources such as satellite-derived Automated Identification System data from ships and relayed to the cloud.

Combining the world’s fiber-optic network with existing remote-sensing systems, like satellites, could create a low-cost global real-time monitoring network, said Martin Landrø, a professor at theDepartment of Electronic Systems and head of the Centre for Geophysical Forecasting. “And we can measure the relative stretch of the fiber extremely precisely,” Landrø said. “It has been around for a long time, this technology. But it has made a huge step forward in the last past five years. So now we are able to use this to monitor and measure acoustic signals over distances up to 100 to 200 kilometers. So that’s the new thing.”

“Although current interrogators are not yet able to sense beyond the repeaters typically used in long fibre-optic cables, the technology is developing very quickly and we expect to be able to overcome these limitations soon,” Landrø said.In the process of detecting whale calls, the researchers were also able to detect ships passing over or near the cable, a series of earthquakes, and a strange pattern of waves that they eventually realized was due to distant storms.

Using these calculations, Landrø’s team identified Tropical Storm Eduardo, which was 4100 km from Svalbard in the Gulf of Mexico. They also identified a big storm off of Brazil, 13,000 km away from the Svalbard cable.Geologists already have a network of sensors that help them monitor and measure earthquakes, called seismometers. These instruments are sensitive and provide a great deal of detailed information, Landrø said.